🔗 Mark Lanegan has been a grunge misfit, a folk-blues drifter and a gutter-dwelling addict. But whenever he appears to sing in that bone-chilling baritone of his, Lanegan is simply known as the gravest voice of his generation.

Mark Lanegan is pissed. At least he sounds that way on the phone, letting out a deep sigh and giving directions to a secluded park near his Southern California apartment. For the third time.

I’m lost and 15 minutes late, so Lanegan—the former Screaming Trees singer, occasional Queens Of The Stone Age member and critically acclaimed, sorely overlooked solo artist—has a reason to burn holes through my handset. Almost as much as I have a reason to shudder at his brusque, end-of-days baritone, bellowing the quickest highway route to Burbank. Even Sub Pop publicity/marketing director Steve Manning admits “he kinda scares me” when asked about how he’s going to handle press requests for the Gutter Twins, Lanegan’s long-awaited project with former Afghan Whigs frontman/fellow Alternative Nation survivor Greg Dulli. Lanegan’s intimidation factor, which is clear from the second his star-tattooed knuckles and tobacco-stained fingers cross your cold, sweaty hand, is legendary.

“I would want Mark on my side in a street brawl,” says Velvet Revolver bassist Duff McKagan. “He’s one of those guys.”

The former Guns ‘N Roses wingman isn’t afraid of Lanegan, though. If anything, McKagan misses the guy; enough that he asks me to put the pair in touch for the first time in more than two years. Turns out that McKagan has riffs he’s saving just for Lanegan, in hopes of returning to the healthy working relationship the two started in 1996, including guest spots on two of Lanegan’s solo albums and a short-lived, as-yet-unrealized project.

“Our paths [in the mid-’90s] were identical in a lot of ways, where we both came really close to the edge of the precipice,” says McKagan. “We pieced it together that we had probably met on the road before, but we were too fucked up to remember where or when.”

Lanegan’s on-again, off-again struggle with drugs and alcohol is nothing new. While he’s currently clean and avoiding bars because “there’s no reason to be there,” themes of addiction and inner turmoil have haunted his songs for years, portraying him as a broken-down character who’s “drank so much sour whiskey I can hardly see” (“One Way Street”), battled “cold chills and shakes, just reminding me of my mistake” (“Waiting On A Train”) and searched for a quick score: “I’d stop and talk to the girls who work this street, but I got business farther down” (“One Hundred Days”).

What is new—and somewhat surprising—is the complex portrait McKagan and others paint of Lanegan, who just so happens to be, in the words of McKagan, “a funny motherfucker, extremely bright with a really whimsical outlook on life. Some aspects of him are dark and brooding, but a lot of that is just his shyness.”

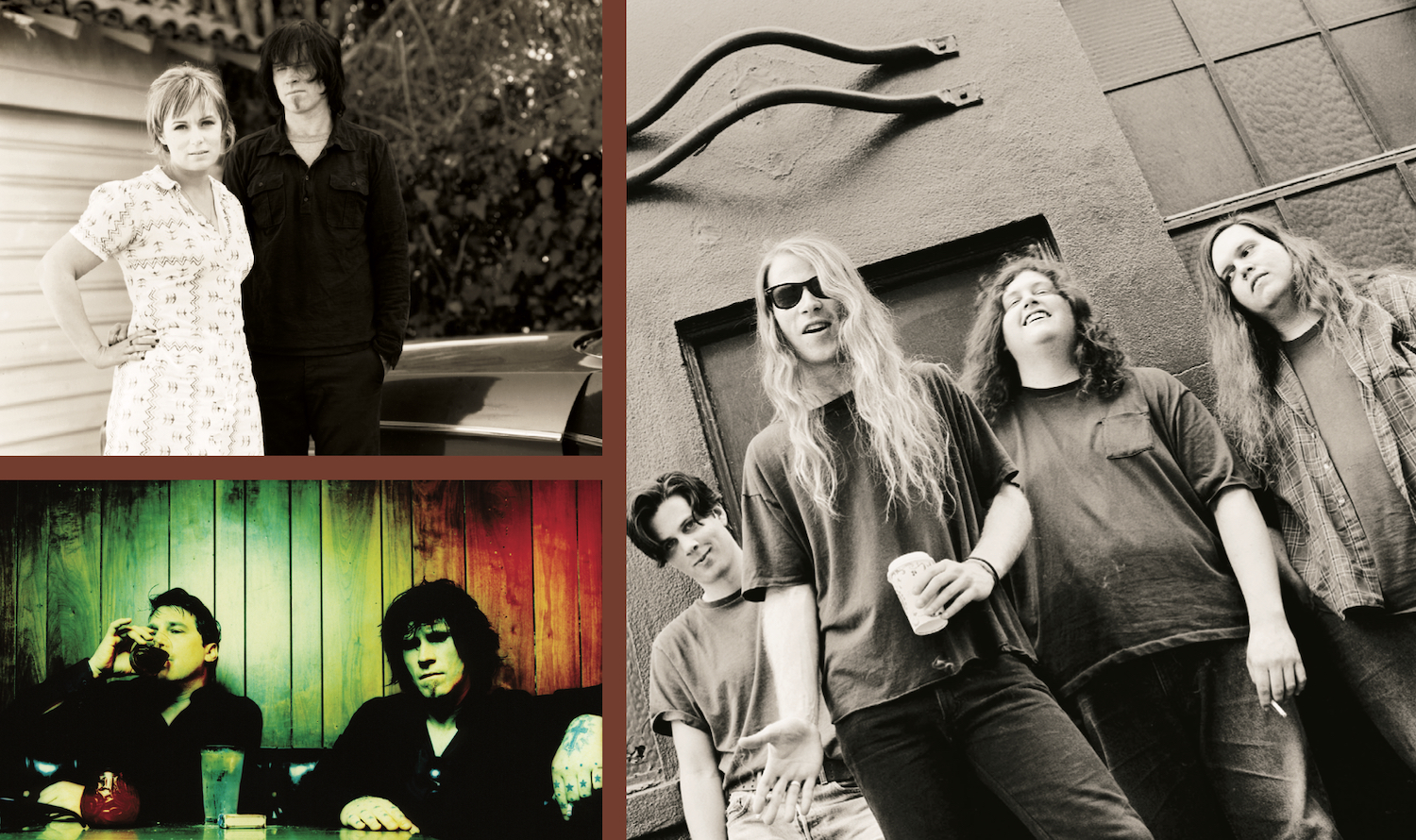

“When we first met, I felt that we had some kind of connection,” says Isobel Campbell, the former Belle And Sebastian member who’s currently finishing the follow-up to her and Lanegan’s Mercury Prize-nominated Ballad Of The Broken Seas. “I can’t really explain it. He seemed gentle, kind and unpretentious to me, which can be a rare thing in the music industry.”

A constant couch surfer worthy of the “Ramblin’ Man” cover he recorded with Campbell in 2005, Lanegan would periodically crash at McKagan’s Seattle home during the mid-’90s. At the time, the bassist’s first child had just been born and Lanegan noticed that the sloping lawn in McKagan’s backyard led down to a creek.

“He was like, ‘You really need to build a fence here, because once Grace gets old enough to walk, she could go down there and drown,’” says McKagan. “I said, ‘I never thought about that.’ He was like, ‘No, you don’t understand. You need to build a fence.’ Needless to say, there’s a fence down there now.”

“Everyone knows about Tom Waits,” says Seattle producer Jack Endino, the man behind the boards for Nirvana’s Bleach, Mudhoney’s Superfuzz Bigmuff, Screaming Trees’ Buzz Factory and Lanegan’s 1990 solo debut, The Winding Sheet. “Why don’t more people know about Mark Lanegan? He’s got one of the greatest voices of his generation.”

“I’m surprised that he hasn’t gotten noticed more, as today’s Johnny Cash or something,” says Soundgarden/Audioslave frontman Chris Cornell. “Maybe he’s too uncomfortable in his own skin to do what it takes.”

Except for the Hitchcockian caws of some nearby crows, the park near Lanegan’s Burbank apartment is eerily quiet. Sitting on a bench, Lanegan looks like he’s awaiting a terminal diagnosis at a doctor’s office: cordial but stiff as a corpse, avoiding eye contact at all costs. His answers are typically terse—a sentence here, a complete thought there—the sign of someone who’s allergic to journalists’ tape recorders.

MAGNET: You hate doing interviews, don’t you?

Lanegan: Yeah, I do.

MAGNET: I thought you didn’t hate me that much.

Lanegan: [Laughing] I don’t hate you, bro. There’s just other things I’d rather talk about.

MAGNET: What’s on your mind right now?

Lanegan: I’d want to know what’s up with you.

MAGNET: Well, I’m stuck writing this story.

Lanegan: That sounds like a bummer. I’m trying to help you, though.

And he does, eventually, beginning with tales of an impressionable teenager stuck in the cultural wasteland of Ellensburg, Wash. It was there, in a college town with a proliferation of AC/DC cover bands, where Lanegan discovered punk rock at a comic-book shop run by a hippie. Sifting through the store’s seven-inches and LPs, he couldn’t help but stare at sleeves by the Ramones, the Stranglers and the Damned. Lanegan traded his entire comic-book collection in exchange for stacks of vinyl, and his hero became Iggy Pop, a chiseled example of embracing the edge for the sake of one’s art.

“I thought to myself, ‘What is this about?’” says Lanegan. “You have to understand that it was very strange for someone in this area of Washington to have that kind of stuff for sale.”

The shop offered Lanegan an escape from a high-school regimen of sports (the former basketball/baseball/football player once told Mojo, “I think I threw the most interceptions in the shortest period of time in the history of our school”) and run-ins with the police. During his senior year, a drug-possession charge landed him in jail, but Lanegan avoided sentencing by entering a treatment program, his first of many stints in rehab.

The only problem with his music obsession, though, was the fact that no one else in town seemed to share it. Lanegan didn’t meet other punk and psychedelic-rock fans until he started taking the bus 100 miles west to Seattle and scouring its record stores. Yet he eventually found a kindred spirit during detention one day at Ellensburg High School.

“The Trees’ bassist was there in a Black Flag T-shirt,” says Lanegan, “which totally blew my mind.”

More often than not, Lanegan refers to his former Screaming Trees bandmates by their roles rather than their names. It’s difficult to tell whether he does this because it pains him to say their names or if he simply assumes we don’t know guitarist Gary Lee Conner from his bassist brother Van, or original drummer Mark Pickerel from his successor Barrett Martin. At any rate, Gary Lee set the Trees in motion by asking Lanegan to operate lights (“a shoebox with switches”) for one of the brothers’ early bands, which did Echo & The Bunnymen and Simple Minds covers at school functions. Lanegan’s grip role didn’t last. Though he initially played drums while Pickerel sang some of Gary Lee’s four-track recordings, Lanegan says it soon became clear he “was such a shitty drummer and the guy that was singing was a great one, so we switched.”

“They had this great, unique dynamic,” says Sub Pop’s Manning, a fan of the Trees since their first Seattle-area shows in the mid-’80s. “You know, Mark being really cool up front while these two big guys rolled around the stage.”

The band named itself after the Screaming Tree guitar pedal, and its fuzz-smeared demo tape was recorded in 1985 by Steve Fisk, who’d go on to produce Nirvana, Soundgarden and Beat Happening. The group’s debut, the long out-of-print and widely bootlegged Clairvoyance, appeared on the Velvetone imprint a year later. Not that anyone in Ellensburg cared, even after Black Flag guitarist Greg Ginn called Lanegan and offered to sign the Trees to his iconic L.A. punk label, SST.

“To this day, that’s probably the most exciting thing that’s happened to me,” says Lanegan. “It was a pretty big deal, especially because guys who wrote original tunes in our town were laughed at by cover bands. If you played the Ranch Tavern, you were a big deal.”

Unfortunately, Screaming Trees’ honeymoon period was over by the time they recorded 1989’s Buzz Factory, their third and final album for SST. Working with producer Endino, the group seemed unsure of its direction. Van Conner had left the band temporarily to tour with Dinosaur Jr, so the Trees tracked, then scrapped, a double album with bassist Donna Dresch before starting over and cutting a single album.

As is often the case with bickering talents, the Trees’ bottled-up tension blew right through the floodgates of Buzz Factory, a grueling grudge match between Gary Lee’s grinding roadhouse guitars and the wailing, whining Lanegan, a still-learning singer.

“Mark would get the worst headaches,” says Endino. “To the point where he’d worry about a blood vessel bursting in his head.”

“We really went nuts,” says Dresch. “Lee would roll around, get cut on broken glass and rub the blood on his face. Mark would sing so hard that all his veins would pop out. Then we would all go backstage and collapse.”

“Gary Lee was kind of hard to talk to,” says Endino. “You get the feeling that there’s a lot going on in his head that you don’t have access to. He’d write 30 or 40 songs for each record, and the guys would pick 10. Four or five of them would sound the same or like (Love’s) Forever Changes, but some of them would be amazing. Mark was the least confident member of the band. As soon as everyone would leave, he’d tell you how much he hated the band and his singing.”

Chris Cornell first met the Trees at a Soundgarden show in Ellensburg, right around the late-’80s release of his band’s buzz-stirring Screaming Life and Fopp EPs on Sub Pop. The Trees showed up intending to laugh at Cornell and Co.’s sludge-slinging metal songs but ended up liking Soundgarden so much that they helped the group get signed to SST. Susan Silver, Cornell’s wife and manager at the time, later returned the favor by securing the Trees a major-label deal with Epic. Cornell co-produced Uncle Anesthesia, the Trees’ 1991 Epic debut, which paled in comparison to the psych-damaged Buzz Factory.

“I look at that record as failing to capture whatever Mark Lanegan is great at,” says Cornell. “Uncle Anesthesia was Mark singing the way Gary Lee wanted him to … He’d be unhappy—really unhappy—and I wouldn’t know why. You gotta give props to Mark for making the songs sound as good as they did. I always looked at Mark as a Kris Kristofferson type, where his heaviest baggage gets carried away with his voice. He’s condemned to a certain way of being, and everyone else benefits.”

Released eight months prior to Nirvana’s Nevermind, Uncle Anesthesia preceded the grunge explosion. But the media hype and wave of public attention headed toward Seattle would catch up to the Trees via 1992 single “Nearly Lost You.” The song became known more for its placement on Cameron Crowe’s Singles soundtrack (which has sold 1.7 million copies) than on the Trees’ subsequent Sweet Oblivion(341,000 in comparison). The arrival of new drummer Barrett Martin (Pickerel left the group in ’91) sped along the writing of “Nearly Lost You” and the rest of Sweet Oblivion. Barrett, formerly of Endino’s Skin Yard, introduced world-music flourishes like hand percussion and the harmonium.

“I remember when I first brought congas to the studio,” says Martin. “Everyone was like, ‘What the hell? Are we venturing into Santana land?’”

Not by a long shot. While not a commercial success on the scale of albums by their Seattle contemporaries, Sweet Oblivion stands as Screaming Trees’ finest achievement. It’s one of the era’s most underrated releases, a record that’s too classic-rock-centric to be directly compared with grunge bands.

“Soundgarden doesn’t have a whole lot to do with Mudhoney, and neither do Screaming Trees or Pearl Jam,” says Endino. “The only thing these bands had in common is no one had any Eddie Van Halens. Gary Lee rolled around a lot, but it was never about his solos or anything.”

The Trees’ songwriting was always tethered to Gary Lee’s guitar, a point of contention that pushed the band into several hiatus periods after opening for Alice In Chains throughout 1992. The support slot was coordinated by Epic after the label abruptly cancelled a headlining run of major clubs and theaters. Lanegan and Martin have divergent opinions on the subject, with the former viewing it as the start of his close friendship with Alice In Chains frontman Layne Staley and the latter seeing it as “one of the biggest mistakes” of the Trees’ career.

“We were a sacrificial lamb giving street cred to Alice In Chains,” says Martin. “It’s not that they weren’t a great band; they just were more metal than us.”

Spinning their wheels on the Alice In Chains tour left the Trees unable to capitalize on the momentum of “Nearly Lost You.” They were on the road for 12 months straight, then went their separate ways to record solo albums (Lanegan issued Whiskey For The Holy Ghost in 1994) and side projects (Martin’s Mad Season featured Staley as its frontman and Lanegan as a guest vocalist ). Dust ended a four-year drought of Trees material and spawned minor hit “All I Know,” but it wasn’t enough to change the band’s dysfunctional dynamic. (While Gary Lee didn’t respond to an interview request, Van initially agreed to talk to MAGNET, then didn’t return emails.)

“We thought we’d made the best record of our career at that point, so we figured we’d just keep going,” says Martin. “One barroom brawl or band argument would lead to everyone saying we fought all the time, but the rumors of inner-band fighting really aren’t true.”

Former Kyuss frontman Josh Homme, the Trees’ touring guitarist from 1996 to 1998, describes the situation differently: “I was the only person who got along with everybody and not because I’m easy to get along with.”

Homme was invited to play on the band’s next album, but he only stuck around for one song before throwing down his guitar in disgust.

“For Mark, the band was like a girl you should have broken up with years ago, where you say it’s over but then you’re slinking back into bed the next day,” says Homme. “It wasn’t my girl, so I was able to walk away.”

Before Homme left, he told Lanegan that he thought the band had reached its logical end and asked him to sing on the 1998 debut by his new band, Queens Of The Stone Age. Lanegan declined, choosing instead to complete another solo LP (1998’s Scraps At Midnight) as well as a long-planned collection of folk covers (1999’s I’ll Take Care of You). He also worked on some Screaming Trees demos in hopes of securing a new home for the band. Epic let the Trees go before their contract was up, as per the band’s request, a decision Martin now blames on poor legal advice.

Martin claims the tracks, recorded in Seattle with producer Don Fleming and the occasional 12-string help of R.E.M.’s Peter Buck, could’ve developed into a Dust-like full-length. Lanegan, however, isn’t so sure. “It might have become something if a label was interested,” he says. “But no one was.”

Screaming Trees played a handful of surprise shows in early 2000 to gauge the industry’s interest one last time. When no significant offers came, they officially called it quits after a June 25 concert celebrating the opening of Seattle’s Experience Music Project.

“I had a sense that the band had run its course and my heart wasn’t in it,” admits Lanegan. “As much as I love those guys, I was through with the band dynamic in the Trees. Tension can lend itself to the creative process, but nowadays I prefer to be tension-free.”

If only Kurt Cobain and Layne Staley—two of Lanegan’s closest friends and occasional collaborators (Nirvana’s unplugged version of “Where Did You Sleep Last Night?” stems from an aborted Leadbelly covers EP with Lanegan, Cobain, Pickerel and Nirvana bassist Krist Novoselic)—had reached the same conclusion about their own drug-addled lives. Cobain killed himself April 5, 1994, and Staley died of a heroin overdose exactly eight years later.

“It’s hard to bury a friend, especially someone who you’ve made music with,” says Martin. “It’s second only to burying a family member. In some ways, it’s worse because you’ve created something with this person.”

Lanegan is tight-lipped on the subject of grunge’s literal and figurative death. When the subject does come up, he simply shakes his head and says there were a lot of “unnecessary deaths” in the Seattle scene. I ask him if he feels like a survivor, if he feels lucky after numerous relapses and rehabilitations due to alcohol and heroin.

“There aren’t too many successful junkies out there, you know?”

Endino says the sessions behind 1990’s The Winding Sheet, Lanegan’s spare and spooky solo debut, were “one of my favorites to work on, and I’ve done more than 300 records. It was magical in that it felt like anything could happen and it’d be good.”

Lanegan is more modest, laughing and admitting, “I thought the idea [of doing a solo album] was ridiculous at first. At the time, I only knew three chords that I picked up from some book.”

Multi-instrumentalist Mike Johnson, Dinosaur Jr’s bassist during its Lou Barlow-free years, was crucial in developing Lanegan’s solo songs throughout the ’90s and early ’00s. Aside from a falling out after 2001’s Field Songs, Johnson has been the only constant in Lanegan’s solo career, sitting by his side for better or for worse on The Winding Sheet, Whiskey For The Holy Ghost and Scraps At Midnight.

No album epitomizes the pair’s relationship—and everything that’s good and godawful about Lanegan—quite like Whiskey For The Holy Ghost. While it’s considered his greatest piece of plastic, Lanegan barely survived its sessions, which stretched on for three years and burned through four producers.

“Part of the reason the first (solo) album went down in a week was because he was clean, I think,” says Endino. “In retrospect, I’m not sure he was (clean) on the second album, which didn’t help all the self-doubt he was having.”

Things got so bad at one point that Endino had to restrain Lanegan from throwing the master tapes into a brook outside the studio. Only Lanegan seems to know just how many ups and downs went into making Whiskey. And, well, he ain’t talking, save for an oblique statement: “I try not to think too much about my past or tomorrow. I focus more on today.” He did admit the following to the Seattle Times in 1998, however: “The only time that I could work, and it got increasingly hard over the years, was when I would stop [doing drugs] for a while … As far as making records or writing songs, it was completely hopeless. That’s why in 10 years I only made three records. It wasn’t something I was capable of.”

Whiskey’s tour rehearsals were almost as tumultuous as the recording process. Says Johnson, “I ended up walking out because Mark was like, ‘Learn these Screaming Trees songs,’ and I said, ‘I don’t want to learn fucking Screaming Trees songs.’ He was pretty pissed that I left, and it’s a serious issue between us to this day.”

The pair patched things up when Lanegan was just out of rehab and ready to record Scraps At Midnight, but the damage was done. Johnson and Lanegan went their separate ways after finishing Field Songs. Shortly thereafter, Homme reiterated his invitation, asking Lanegan to join Queens Of The Stone Age full-time after he contributed lead vocals to Rated R’s striking “In The Fade.” Lanegan has since toured with the band and appeared on every Queens album.

“The first year he was on tour with us, I thought he didn’t like me because he’d leave the room a lot,” says Queens bassist/vocalist Nick Oliveri. “Josh was like, ‘Nah, he likes you. It just takes him a long time to open up.’ I figured I better stay out of his way, then, because I wanted him to keep singing with us. Things were perfect every time he came onstage.”

Eventually, Lanegan and Oliveri became inseparable on the road, bonding over coffee and playing impromptu acoustic gigs at record stores along the way. Oliveri was booted from Queens in 2004 after excessive partying and the alleged physical abuse of his girlfriend; Lanegan asked to leave the band’s touring lineup the next year, citing “health issues” and the need to record another solo album.

“He was unhappy with the lifestyle,” says Lanegan’s ex-wife, musician/actress Wendy Rae Fowler, who met him in 1998. “He went into that [spring 2005 tour] clean and sober, and came out of it very not.”

Homme is understandably vague when asked about indirectly encouraging Lanegan’s self-destructive behavior. “Mark’s always struggled with pushing down his bad side because it’s big and it’s bad,” he says. “Shit, it’s been hard for me because I never wanted to discover Mark not being on this earth anymore. Thank god he’s like a cockroach and can’t be killed.”

“Very few songs in the world can make me break down at any moment,” says Homme. “‘One Hundred Days’ is one of those songs.”

Homme is talking about one of the standout tracks from Bubblegum, the 2004 full-length debut by the Mark Lanegan Band, a loose collective of L.A.-centric musicians including McKagan, Oliveri, Dulli, Polly Harvey and assorted musicians from the Queens Of The Stone Age camp.

The Bubblegum sessions went through multiple producers and took place in nine different studios. Eventually, Lanegan bashed out nine songs in two days with the help of Homme and Dave Catching at the latter’s Rancho De La Luna studio in Joshua Tree, Calif. “It was like magic after a pile of trash,” says Homme.

Catching and Homme took turns playing bass, guitar and drums, while Lanegan sweated profusely and barked out songs such as “Hit The City” (a duet with Harvey) and the manic “Methamphetamine Blues.” Not only did Bubblegum stand in stark opposition to the tumbleweed folk of his past solo work, but Lanegan sounds as if he’s losing his mind on the record. As Homme puts it, “It’s as if Mark is sitting with a shotgun on his lap waiting for someone to come home.”

He very well might’ve been. Lanegan and Fowler were reaching the end of their marriage by the time of Bubblegum’s completion, something she’d sensed soon after they got married in 2002 and relocated to rural North Carolina. The couple had moved to Fowler’s hometown to get away from L.A. and a shared, post-September 11 malaise, but Lanegan left for a Queens tour the day after their wedding.

“That was pretty much the end,” says Fowler, who’s currently working on a record with ex-UNKLE collaborator Richard File. “He left for tour, and I was stuck standing there with my dick in my hand, saying, ‘What do I do now?’”

Fowler is grateful to Lanegan for two things: his encouraging demeanor (“I appreciate that he accepts the beauty in the awkwardness of life,” she says) and the music, books and films he shared with her, from Galaxie 500 and Lee Hazlewood to the surreal poetry of Chilean icon/communist politician Pablo Neruda.

“He’s very careful about who he shows himself to,” she says. “But if he decides he likes you, there’s some fun to be had, because he’s got a great sense of humor and a large heart.” She pauses. “Being around him was a constant learning experience. In a lot of ways, he’s wise because he’s been around the block a few times. I’m not a religious person, but sometimes when he speaks, he sounds like a prophet.”

As the sun begins to set in Burbank, I’m struck by how little Lanegan has said in the two hours we’ve been sitting in the park, watching horses from the nearby equestrian society trot by. He’s terse but not rude, and his patience and contentedness either stem from sobriety, domestic bliss (he’s currently living with his girlfriend) or the peacefulness of our surroundings.

“Everyone in life has their ups and downs, man,” says Lanegan. “I don’t know when my last [down] was, but I’m definitely happy right now.”

Another reason for Lanegan’s improved mood could be that he finally finished Saturnalia, the full-length debut of the Gutter Twins. Arriving after years of collaborating—mainly via Dulli’s Twilight Singers, who Lanegan toured with throughout 2006—the album is poised to bring both artists some long-overdue respect from a twentysomething audience too young to remember the Trees or the Whigs.

Listening to unmastered versions of four Gutter Twins tracks on Lanegan’s iPod—as the singer stares into space and smokes what must be his 10th cigarette in an hour-long chain—it’s some of the strongest material from either camp in years, offering a potent, spiritual blend of R&B, soul, gospel and the blues. In some ways, it’s a natural progression from Lanegan’s work with the Soulsavers. Lanegan originally signed on as a guest singer for the U.K. trip-hop outfit’s recent It’s Not How Far You Fall, It’s The Way You Land but ended up on eight of the album’s 10 tracks, including a haunting cover of Whiskey For The Holy Ghost cut “Kingdoms Of Rain.”

“The only criteria we had [with the Gutter Twins] was that it needed to be different from everything we’ve each done before,” says Lanegan. “Otherwise, what was the reason to do it?”

“Whenever we started to go into one of our comfort zones, the other guy would throw a bucket of cold water on him and say, ‘Snap out of it, boy,’” says Dulli. “Neither of us would have done this alone. It’s unique to the two personalities involved.”

If Oliveri thought he had it bad, waiting a year for Lanegan to warm up to him, try being Dulli. Cobain and Novoselic introduced the two at a house party in 1989, and they “didn’t hit it off at all,” says Dulli. A decade passed before the two crossed paths in L.A. and decided to have lunch together. Soon after, Lanegan started showing up at Dulli’s house to listen to records and hammer out acoustic cover songs on the back porch, some of which ended up on the Twilight Singers’ She Loves You.

“I can see how some people find it hard to get close to him,” says Dulli. “I don’t know him that way, though. I only know him as this funny, engaging person who’s frequently lost in his thoughts. Like he’ll be looking out the window, but you can tell the gears are turning.”

As for Lanegan’s mental and physical health, Dulli adds, “This is the best version of Mark that I’ve ever seen. I’m sure he has his low moments, but he’s very well-adjusted right now.”

Well-adjusted for Lanegan, that is. He’s still one of the most shadowy, mysterious personalities in rock music, a guy Endino characterizes as a “total misanthrope.”

Says Homme, “If you’re in a roomful of people and wondering where Mark is, he’s usually standing on the other side of the doorway looking in—literally. He is an outsider on purpose. I’ve always loved that about him. He is, and I say this lovingly, the meanest nice guy I know.”